What is research?

Dr Victoria Kelley explains

At UCA, as at all universities, many of our staff and students engage in research. But what is research in a specialist art and design University? How do we do it and what does it result in? We asked UCA's Director of Research, Victoria Kelley, to write a guest blog to answer all these questions and more.

04 Apr 2022

/prod01/channel_8/media/marketing-media/blog-imagery/web-SkettyHallWedding_Final_01-1199X800-(1).jpg)

Image above, Sketty Hall Wedding by Prof. Anna Fox

A simple and common definition of research, in all disciplines, is that it is a process of investigation leading to new insights, effectively shared. This definition applies to medical researchers working in the lab to develop a better drug to treat a disease, to environmental scientists using computer models to deepen our understanding of changing climate and to historians searching the archive for new evidence to understand a historical event. In art and design, it applies to creative practitioners working at the experimental edge of their disciplines to discover or create something new. At UCA we have researchers who are fine artists, filmmakers, craftspeople, photographers, sculptors, composers, performers and architects, and who are writers investigating the history and theory of all of those disciplines, and more.

Let’s think a little further about that definition of research, breaking it down into those three tenets.

Professor Victoria Kelley

Process

Research is a process, and doing research has to be a deliberate and orderly activity. It almost always starts by identifying a gap or a need, an area of knowledge that nobody has explored before or a question to which no-one has a good answer. To recognise the gap, it is necessary to know about your field and what other people have done and are doing. It is also necessary to have specialist knowledge and training to decide on the best methods and techniques to use to fill that gap. All research starts with a clear idea of what needs doing and how to start doing it. Research is never accidental - but it may well be creative, inventive and insight-driven, developing and changing as the researcher responds to their initial findings and starts to think and investigate in new ways.

Take two of our researchers as examples.

Photographer Professor Anna Fox’s research project The Moon and a Smile started in the archive of pioneering 19th Century photographer John Dillwyn. Recent discoveries had shown an important gap in understanding, namely that many of the photographs attributed to John Dillwyn were in fact by his daughter, Mary Dillwyn. The Dillwyns, a wealthy family, took many of their photographs in their private home and estates in South Wales. Fox re-photographed sites pictured by the Dillwyns, inserting her work as a prominent female photographer into this history of gender under- and over-representation. She also revealed the social changes that have resulted in the private, privileged sites the Dillwyns photographed in the 19th Century becoming public spaces of leisure for all classes. And she used innovative techniques to digitally stitch together multiple images to disrupt the notion of the photograph as capturing a single moment in time.

Above, another photograph by Prof. Anna Fox as part of her The Moon And A Smile research project

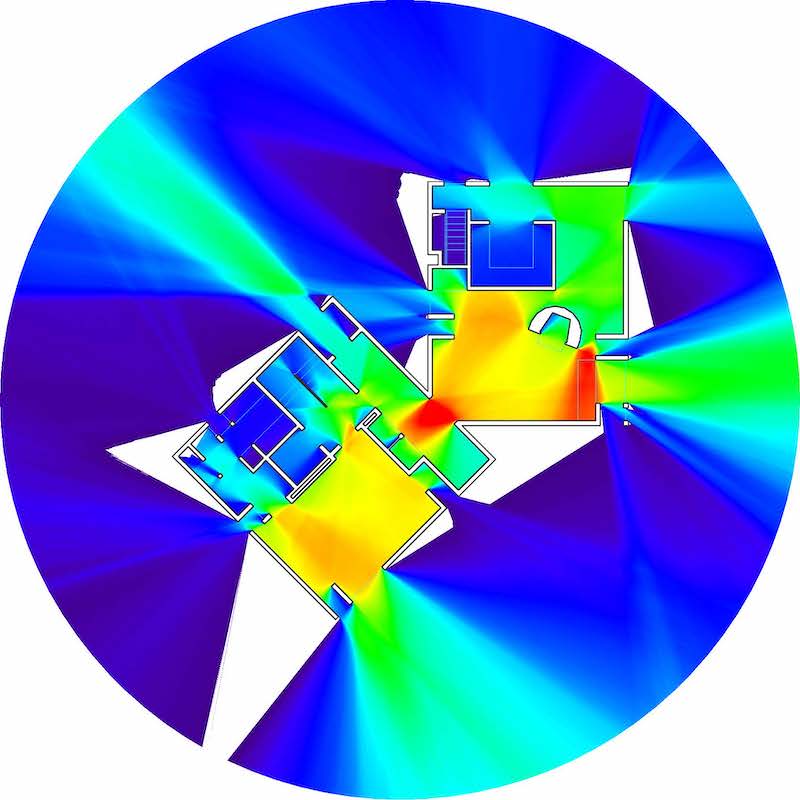

Meanwhile, architecture researcher and UCA Programme Director Sam McElhinney identified a problem with the existing software used by architects to analyse how people will experience the buildings they are designing. McElhinney took an innovative digital approach to spatial analysis and developed it into his Isovist_App software that processes spaces more quickly and more effectively, giving architects an improved design tool.

An image generated by the Isovist app, created by Sam McElhinney

New insights

Starting the research process by identifying a gap to be filled or a question that needs answering means that research always aims to uncover something new. At UCA, students at all levels conduct research, and for them, the ‘something new’ they are pursuing can be simply something that is new to them, as they engage in the exciting process of increasing their own knowledge. Our staff researchers are at the leading edge of their disciplines, creating insights that are new in absolute terms, pushing forward the boundary of knowledge and producing fundamental research or experimental approaches characterised by great originality. The original contribution that comes from research might be in a very defined area. It isn’t necessarily going to change the world, but it will have the potential to change a small part of it, or our understanding of it. An example is the work of Professor Martin Charter on the worldwide repair café movement. Repair cafés take broken items (from kettles to cardigans) and repair them for their owners; the Carbon Calculator developed by the Farnham Repair Café which Charter co-runs is an online tool that enables repair cafés everywhere to measure the quantity of carbon emissions saved as a result of each repair they do. The result is a simple but powerful new way to collect evidence to campaign for the ‘right to repair’ and the circular economy.

Effectively shared

And finally, we come to effectively shared. Research is of no use if no-one knows about it, and it should always start with an idea of who the audience will be. Research audiences might be big or small; sometimes the primary aim of a research project is simply to reach and influence other researchers and contribute in turn to their knowledge. My own research is in the field of the history of design and material culture, and in a recent research project I investigated the history of London’s street markets. No-one had looked at these markets in any detail before, and my 2019 book on the subject therefore contributes new insights. Although the book is accessible to anyone interested in urban history, its main audience is the relatively small one of other historians, students of history, and academics. I know from reviews of the book in academic journals and citations of it in the writings of other historians that it has reached this audience successfully. For many of our researchers, however, their audiences are large public ones; Professor Lesley Millar’s research is as a curator in the field of textiles. From 2016 to 2018, she created a series of exhibitions that demonstrated how tapestries are still, in the modern world, an important medium for telling stories and communicating messages. These exhibitions reached more than 300,000 people at four venues across the UK.

One of the ways we judge the success of our research is through its impact. Impact goes one step further than the issue of whether research has been effectively shared by assessing what change has it brought, or difference has it made to the people who have experienced it. Prof. Fox’s The Moon and a Smile project was part of her wider research into the disadvantages women have faced and continue to face in the photography industry, where their work is less likely to be published and bought by galleries and collections. She leads the Fast Forward network, which campaigns for change in this field. Fast Forward’s work has led the Hyman Collection, the most important private UK collector of photography, to make a public commitment to ensure that 50 per cent of the work it buys is from female creators - a real and important change brought about by UCA’s research and researchers.

UCA is all about creating - making, designing, imaging, crafting - in ways that make a statement, that challenge convention and that contribute to making a difference to the world. These principles are the same for students and researchers, and we are always excited to see the seeds of new research sown in UCA’s campuses when students discover new ways of thinking and working in their creative journeys, sharing their ideas in exciting ways. What will you discover on your UCA course?